I know, I know, I hear you now: “go find your own favorite statistician!” The thing is, Nate Silver is not only brilliant with numbers, but he also has thoughtful, well-developed ideas and he articulates them well.1 Silver knows his stuff, and he makes it fun to learn about. If you haven’t read any of his blogs or his book2, you are in for a treat. He gets me all riled up about the fact that we have some much information yet so little knowledge. He’ll get you excited about figuring out how to make sense of heaps of data. He’ll show you how awesome numbers are.

It’s like math orgasm.

Obviously

Nate gets lots of bonus points for being not only a numbers guy but ALSO a

words guy. In the intro to his book, he talks you through the etymology of

“prediction” (Latin roots, with a superstition-kinda-fortune-telling connotation)

and “forecast” (Germanic roots, implying prudent planning despite uncertain

conditions). Forecasting is definitely progress, when that is actually what we

are doing, since it means using what we already have to make more educated

guesses. And yet, we’re still addicted to prediction, even though we’re embarrassingly

inept.

I

wonder if part of what will make us better forecasters is recognizing how biased

our predictions are by our own confidence. As Silver puts it, “Human beings

have an extraordinary capacity to ignore risks that threaten their livelihood,

as though this will make them go away.” We all do it, and to a large extent I

think this can be a positive thing. I mean, let’s face it, if we really stopped

to think about every last obstacle that could possibly derail our plans, it

would be much more difficult to get up with a smile each day. It’s nice to feel

able and self-sufficient, and there is good evidence that those who approach

tasks – intellectual or athletic ones – with confidence are those who often end

up more successful. No one likes arrogance, though, and it’s a fine line that

divides the confident from the arrogant.

Nate comments at one point that “most

of our strengths and weaknesses as a nation – our ingenuity and our industriousness,

our arrogance and our impatience – stem from our unshakable belief in the idea

that we choose our own course.” And we

should be better at controlling our fate in this data-rich era, right? Maybe

not.

“We think we want information when we really want knowledge.”

“We think we want information when we really want knowledge.”

With modern technology, we have access to more, but unfortunately “if the

quantity of information is increasing by 2.5 quintillion bytes per day, the

amount of useful information almost certainly

isn’t. Most of it is just noise, and the noise is increasing faster than the

signal. There are so many hypotheses to test, so many data sets to mine – but a

relatively constant amount of objective truth.” Last week, we talked a bit in

our summer journal club about the possibility of completely “null fields”; this

is the idea that there are whole branches3 of science in which we

are looking for relationships that simply don’t exist. It’s a big question, to

be sure, and the distinction between statistical significance and genuine relevance is of obvious importance.

We’re a bunch of twenty-something-year-olds talking through this stuff, and

we’re not quite presumptuous enough to come to any conclusions, but it’s

interesting to think about.

Another

major issue we’re up against is the necessity for building assumptions into our

models. A question as simple as “are these events independent or not?” can

change your whole analysis of risk. Mathematically, it becomes obvious right

away what a dramatic difference the extent of the dependence can make4.

In the real world, we don’t always know if the events are independent or not;

further, even when we know they’re not independent it’s pretty difficult to

quantify how related they are. “Risk” is the stuff that’s quantifiable: “I have

a 1/20 chance of selecting the blue.” Uncertainty, though, is the risk that is

hard to measure. When we build models and forget to admit just how much

uncertainty there really is, we end up forecasting in a range that might be too

narrow. It’s tricky to keep track of the difference between what we know and

what we think we know, seeing as we don’t know which is which. This partially

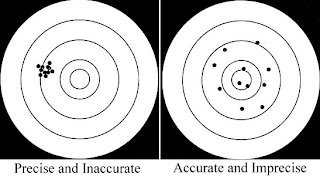

explains why we have a nasty habit of making predictions that are absurdly

precise but not at all accurate.

Too

often, we convince ourselves that certain bad outcomes are simply not possible.

Let’s remember what Douglas Adams said in The

Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy: “The major difference between a thing

that might go wrong and a thing than cannot possibly go wrong is that when a

thing that cannot possibly go wrong goes wrong it usually turns out to be

impossible to get at or repair.”

So…that’s

that for today. I’m pretty excited about math, I think staying humble makes us

better forecasters, and I’m curious to hear what you think about statistics in

the Real World!

1 That last part, that part about expressing them...it’s not

trivial. No one really wants to talk to a mathematician or a scientist who

speaks their own language and can’t use normal words.

2 In 2012, Silver published his first book, The Signal and

the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail – But Some Don’t, and he currently writes the blog FiveThirtyEight as part of The New York Times, available at http://fivethirtyeight.blogs.nytimes.com;

unless otherwise noted, quotes in this post are from his book.

3

or

sub-disciplines of sub-branches or whatever…don’t want to offend anyone

4

If

you have independent events, you simply multiply the probability of each event

occurring to find the probability that they all occur simultaneously, i.e. P(A

and B and C) = P(A)*P(B)*P(C). However, if the occurrence of some of the events

depends on the others, you have to know how likely the second event is to occur

given that the first already has, i.e. P(A and B) = P(A)*P(B|A). There are lots

of great examples we could talk about using anything from economics to medical

diagnosis, but you already get the idea.